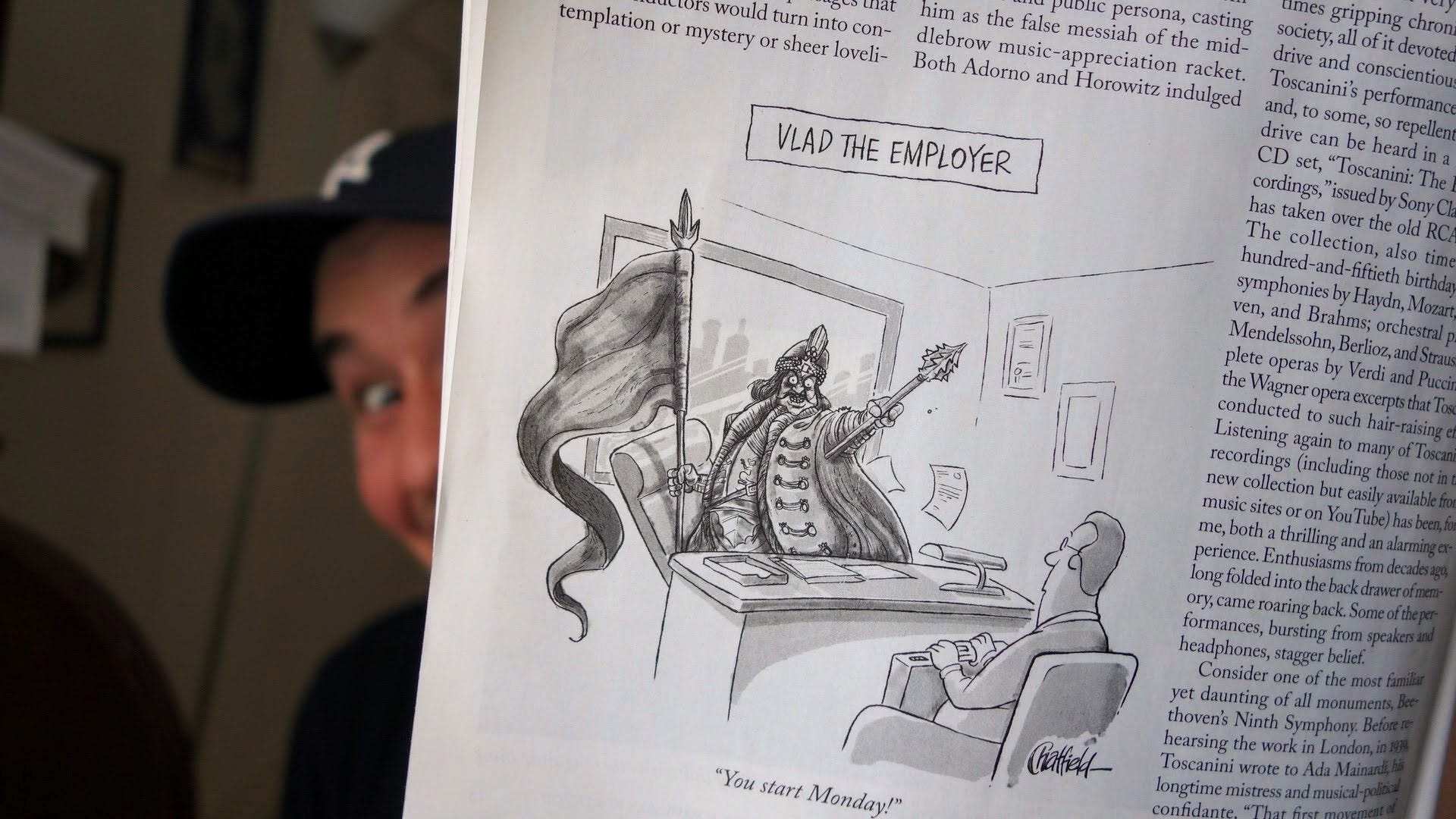

The first time I was published in the New Yorker was the most amazing thrill. A career highlight. Nothing will beat that feeling of seeing my drawing and idea printed in the pages of a magazine I’d been reading since I stole copies from my Dentist’s office in Perth. (Sorry, Dr Farrugia).

But there is an aspect …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Process Junkie to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.