There's a particular sweet spot in the art of cartooning…

That perfect moment when your reader's eyes widen, and they let out an involuntary snort. I once saw it happen in real time while sitting on the Subway, watching an old man next to me reading a

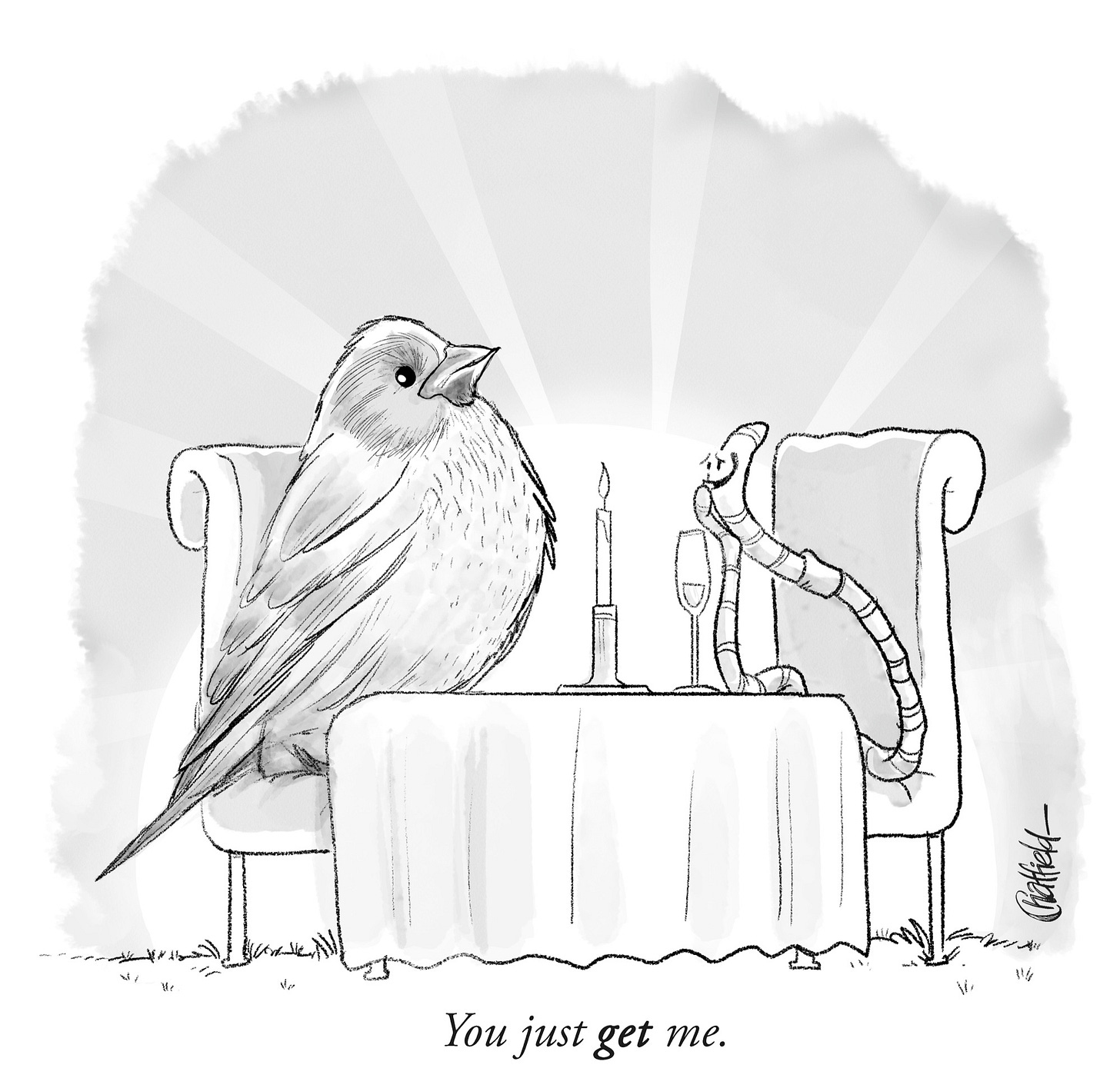

cartoon in the New Yorker. That private little moment is why I still drag myself to my drawing board each morning, surrounded by empty coffee cups and half-finished sketches about talking dogs and dinner party guests: I want to find the elusive ‘perfect joke’ that elicits a very specific kind of response. I want to make my readers feel like they ‘figured out the puzzle themselves.’When I was still living in Australia, I devoured every book on cartooning I could find. There was no SVA, No SCAD, or CAL Arts— we didn’t have Peter Kuper or Bill Griffith teaching comics or illustration in Perth: we just had “Amazon Books”1 and a library card. I'd sit on the floor of my studio apartment for hours, flipping through dusty tomes on the floor, searing for the perfect gag. But nothing—absolutely nothing—has been as valuable as the whispered wisdom from working cartoonists in New York (usually in dimly lit bars) after rejection-heavy days. I discovered that you learn more from other working cartoonists than from any book you’ll ever read.

The most consistent advice I've received?

"Let the reader arrive at the punchline themselves."

It seems simple, but it's maddeningly difficult to execute. Don't hand-hold. Don't overexplain. Don't condescend. If they get it, fantastic. If they don't, well, sometimes that's on you (rewrite, redraw, rethink), and sometimes, it's just not their particular brand of humour—like how my Australian references about ‘Tim Tams’ fall completely flat at New York comedy shows. (IYKYK)

I've spent countless sleepless nights trying to locate that magic balance between "too obscure" and "too obvious."

The advice above came from the inimitable and prolific Sam Gross— the most consistent ‘captionless’ gag cartoonist I’ve ever met. He proved that the format of a great gag cartoon is an art form all in itself.

Related Reading:

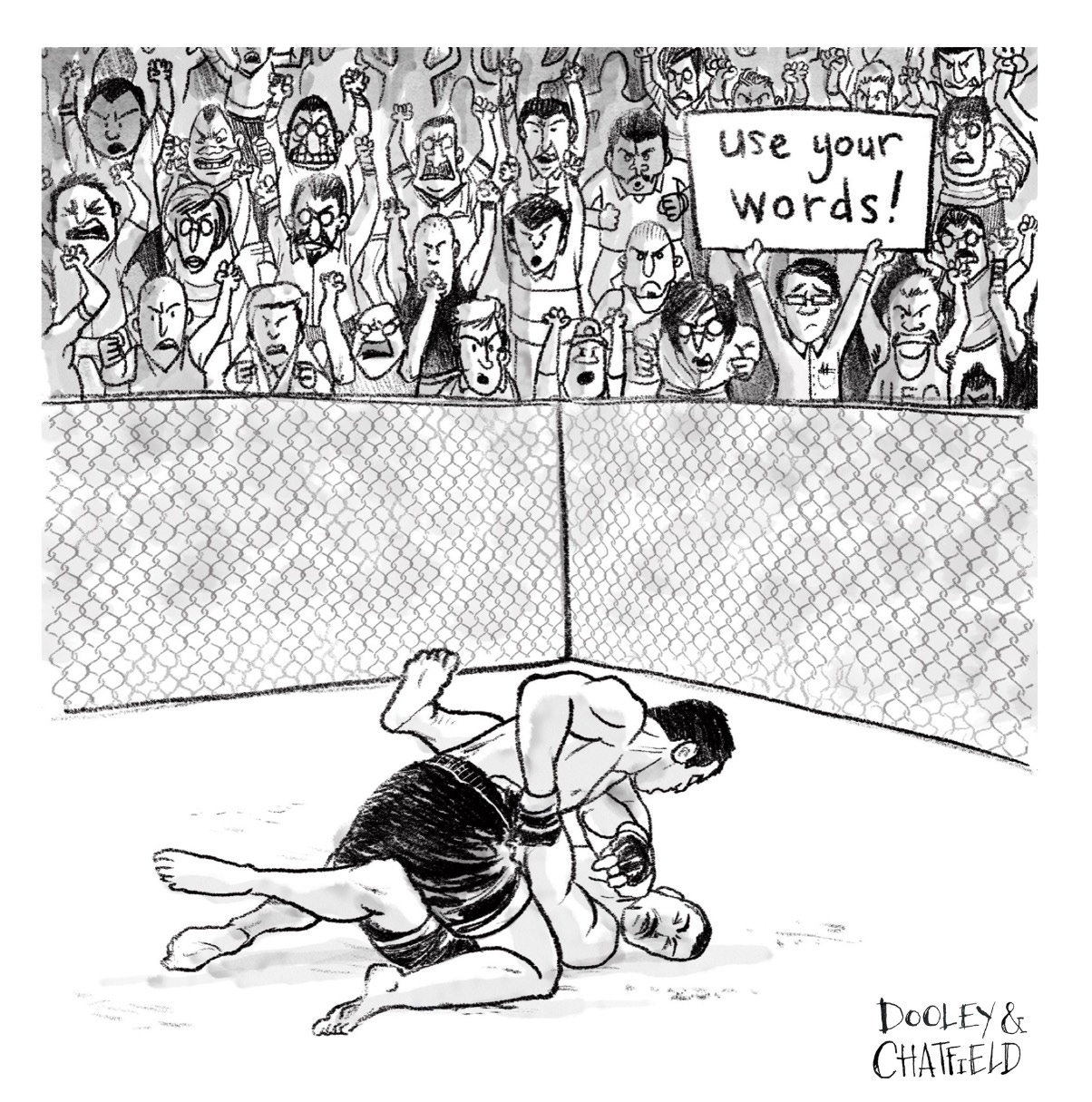

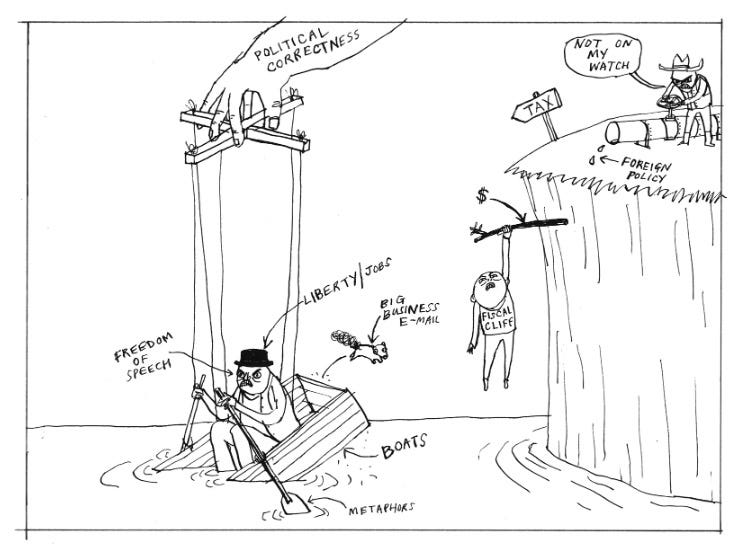

My writing partner Scott coined a term for cartoons that beat you over the head with their messaging—where everything is labelled like a Ben Garrison political cartoon. You know the type: a massive ship labelled "S.S. ECONOMY" headed for an iceberg called "RECESSION," sometimes with a captain wearing a "PRIME MINISTER" sash.

When our ideas drift into this territory, one of us will grimace and mutter, "That's a bit S.S.," and we invariably toss it. If you have to put a politician’s name on their briefcase, you need to go back to the drawing board.2

(In fairness to editorial cartoonists, sometimes labels are necessary when your work is syndicated globally or translated. Sometimes, you need that newspaper blowing through the scene with the relevant headline just in case the paper running your cartoon hasn't covered that story. This could be avoided if papers hired local cartoonists to draw about local issues, but those days have gone the way of three-martini lunches.)

The incredible Ed Steed did a Daily Shout parodying this practice in the New Yorker 7 years ago. You can read that here.

Finding this balance is something I still struggle with daily.

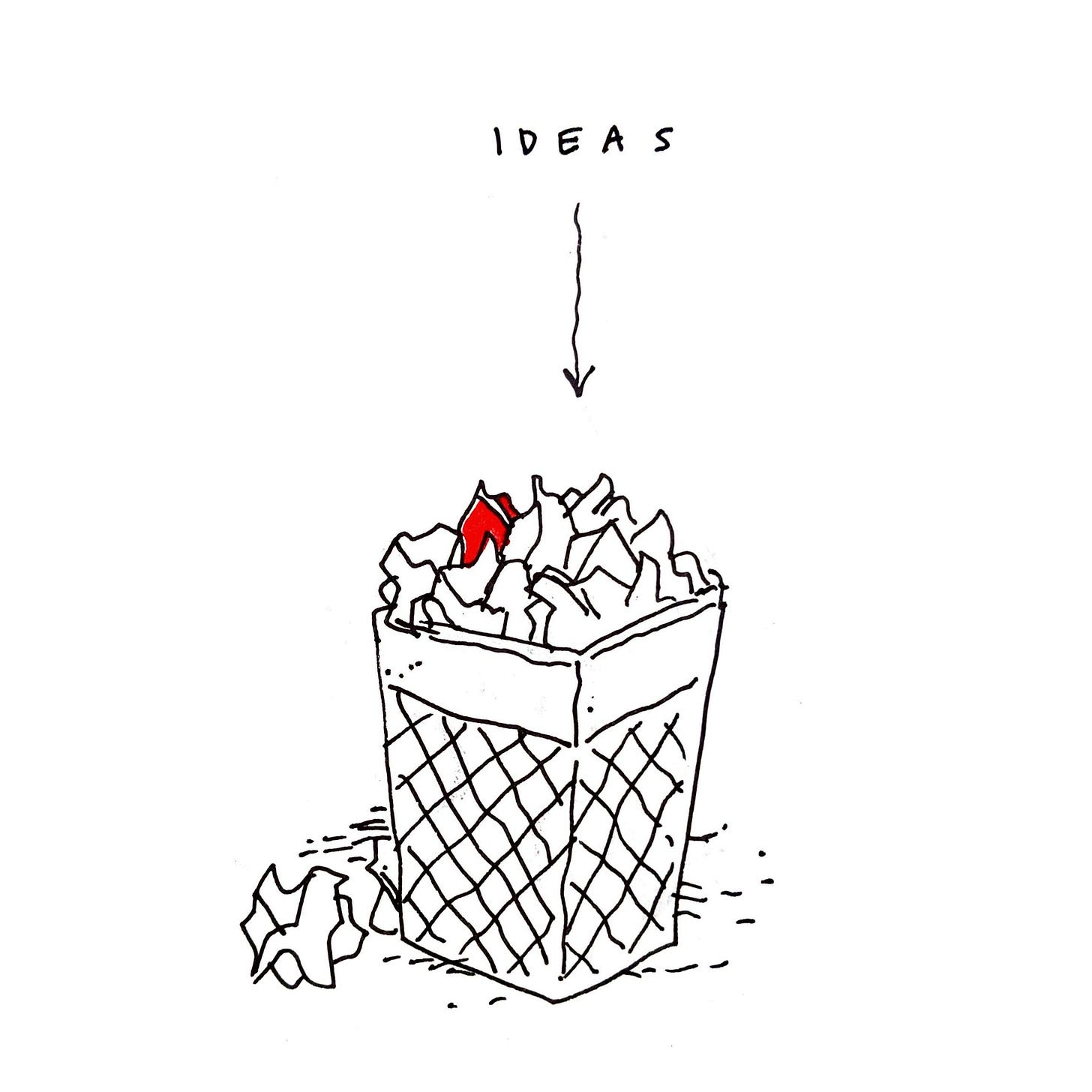

Just last week, I spent three hours redrawing a cartoon about New York real estate because I worried it was too obvious. I'd drawn a Manhattan broker showing a literal closet to a prospective tenant while saying, "It's technically a junior one-bedroom." My original draft had way too much set-up, and by the time I drew it up, it felt clunky, so it ended up in the wastepaper bin. It may find a new life as something else. (You never know when an idea might bubble back up and make an unrelated idea better. We’ll cover that in the coming weeks.)

The key to finding the balance lies in leaving a trail of breadcrumbs for the reader to connect the image to the caption (if there is one) and land the plane on their own— they need to arrive at the punchline without you necessarily handing it to them on a platter. Surprise is an essential comedic tool, and there are several (some say seven) comedy formats to play with on the joke-writing plane, but the biggest thing to remember is: don’t treat your reader like an idiot. Let them get there themselves.

The human brain is designed to recognize patterns— trust that if you draw the cartoon correctly, their brain will do the thing it’s meant to do and solve the puzzle you’ve set. You could be a complete obsessive and even use the Golden Ratio if you really want to lead their eye around an image to have it land where you want it to, when you want it to, but not everyone can be as much of a geek as me. (I should really get a hobby. I hear pickleball’s fun.)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Process Junkie to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.